It’s no secret that IPython is my favorite Python shell. I am the guy who is always asking everyone “did you try IPython already?” as soon as I see they opening the regular Python shell. Yes, I know, you’d probably hate me.

The reason I like it so much is that IPython makes it very easy for me to incrementally experiment when coding. I consider experimentation to be a crucial step when writing software, as it helps to reduce the unkowns in a problem or technology.

Whenever I feel that there are gaps between what I know and what I have to accomplish, I use IPython to run experiments. After a bit of fiddling, I usually have a better understanding about what I have to do and then I feel more confident to go ahead and design a solution.

IPython provides me with the tools that I need for easier experimentation and I will share my favorite ones here.

Docstrings and source code at your fingertips

REPLs like IPython are the perfect environment for experimentation. One of the things that I need the most when trying stuff in IPython is to understand the functions/modules that I am willing to employ, and there’s nothing better than docstrings to help me with that.

IPython brings a handy shortcut to view the docstrings from any object. All I have to do is to append ? to the object’s name and hit enter. Check this out:

>>> os.getenv?

Signature: os.getenv(key, default=None)

Docstring:

Get an environment variable, return None if it doesn't exist.

The optional second argument can specify an alternate default.

key, default and the result are str.

File: ~/.virtualenvs/python3/lib/python3.7/os.py

Type: function

However, sometimes I need to dig a bit further because the doctstrings are not clear enough or because I want to make sure that a corner-case is covered. Reading the source code is usually the best approach for that and IPython makes it pretty easy for pure-Python functions/classes/modules. It’s just a matter of appending ?? and hitting enter:

>>> os.getenv??

Signature: os.getenv(key, default=None)

Source:

def getenv(key, default=None):

"""Get an environment variable, return None if it doesn't exist.

The optional second argument can specify an alternate default.

key, default and the result are str."""

return environ.get(key, default)

File: ~/.virtualenvs/python3/lib/python3.7/os.py

Type: function

Saved results for faster experiments

I find myself very often in a situation like this: I just executed a statement, saw the result and then I want to reuse that value in a follow-up statement. You’ve probably been there already too. The first instinct is to just re-execute that expression, now assigning a name to it so that you can reuse it in the next statement.

The good news is that we don’t need to do that. IPython saves the results of the 3 latest statements in these 3 names: _, __ and ___ (most to least recent).

>>> 1

1

>>> 2

2

>>> 3

3

>>> _ + __ + ___

6

>>> _ * 2

12

IPython also allows you to refer to the result of any statement previously executed in the current session via their numbers using the _n syntax. Check this out:

In [18]: 5 ** 2

Out[18]: 25

In [19]: _ * 4

Out[19]: 100

In [20]: _19 + 2

Out[20]: 102

I actually customized my prompt to not show these numbers, so this is not useful for me. Also, a long session with large output objects may bloat your computer’s RAM. To avoid that, you can always disable caching by addding this to your IPython configuration:

c.TerminalInteractiveShell.cache_size = 0

This won’t disable the handy _, __ and ___ shortcuts, though.

Magic commands

IPython supports a variety of builtin commands that are so handy that they’re called magic commands. They all start with the % prefix and serve the most varied purposes. I am not a magic commands power user, but there are a few that I see myself using every now and then.

%timeit: timing your python code

One of the goals of experimentation is figuring out what’d be the best solution to a particular problem, and often deciding what’s best involves performance evaluation. The timeit standard library module is great for that as it allows for measuring the time taken by a statement.

With IPython it’s even easier, as you can use the %timeit magic function:

>>> %timeit [x for x in range(1000)]

33.4 µs ± 238 ns per loop (mean ± std. dev. of 7 runs, 10000 loops each)

%prun: profiling your python code

When timing the execution of a given statement is not enough for the experiments, profiling it is the next step. IPython provides the %prun magic command to allow for that. Check it out:

>>> %prun get_players_with_most_championships(players)

11 function calls in 0.000 seconds

Ordered by: internal time

ncalls tottime percall cumtime percall filename:lineno(function)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {built-in method builtins.exec}

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 ipython_edit_s94fadw6.py:1(players_with_most_rings)

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {built-in method builtins.max}

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 <string>:1(<module>)

4 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {method 'append' of 'list' objects}

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {method 'keys' of 'dict' objects}

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 {method 'disable' of '_lsprof.Profiler' objects}

1 0.000 0.000 0.000 0.000 ipython_edit_s94fadw6.py:7(<listcomp>)

This is great, as it helps identifying possible bottlenecks in the statements that I am experimenting with.

%edit: editing snippets in my editor

It’s a pain to write an entire function directly in the shell input. Fortunately, the %edit magic function allows me to do that in my favorite editor. Once I close the editor, IPython will execute whatever I have typed in there.

Check this out:

And if I want to reopen the same snippet for editing, I can just execute %edit -p and that very same code snippet will be back in my editor.

This magic command is super handy when you want to input a big function and need a better place to write it in than the IPython shell itself.

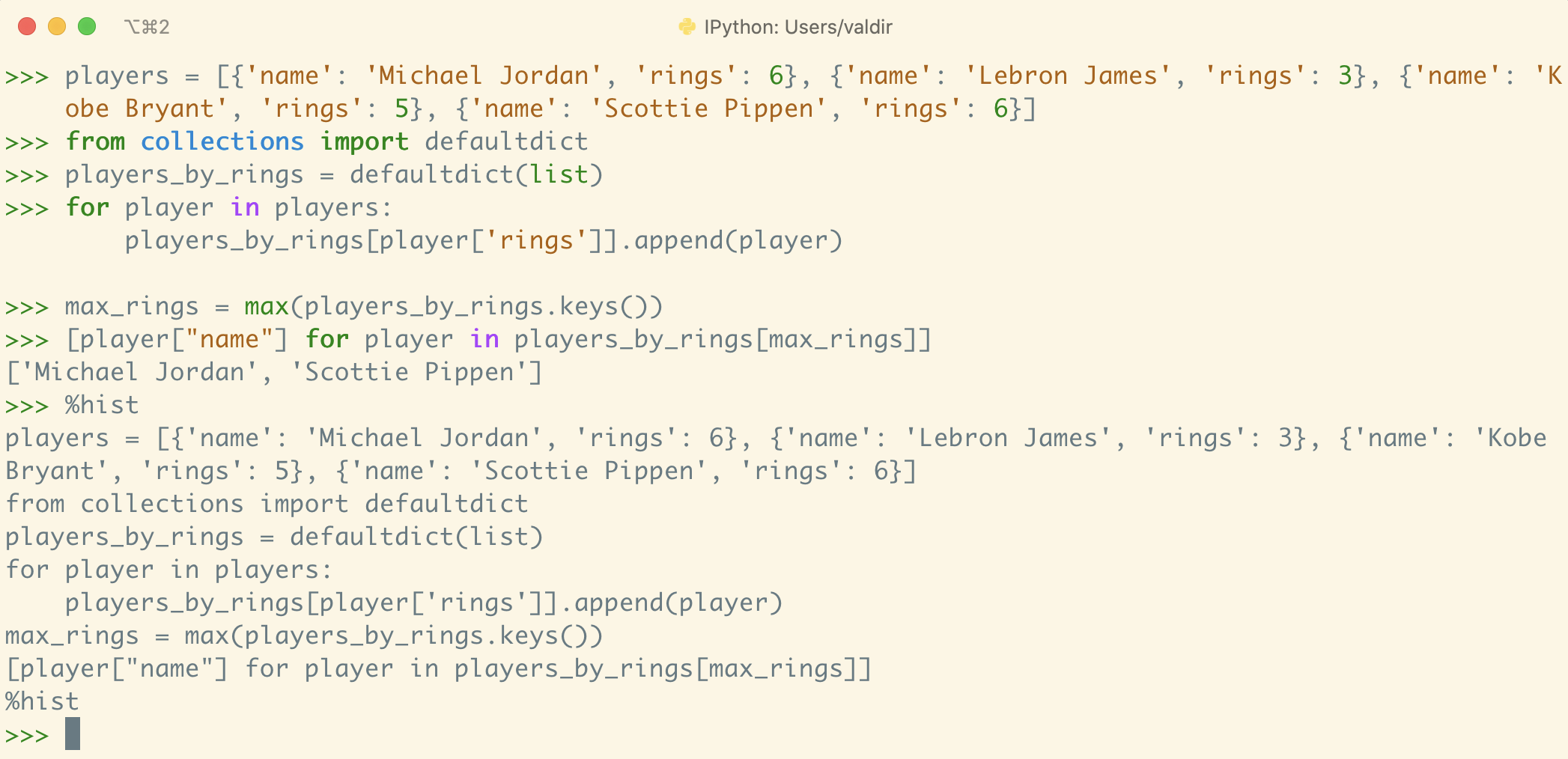

%hist: listing the commands history

When I am writing a function for an app and I am not really sure which operations are needed to transform the input from one format into another, I just open IPython and start experimenting. After a few experiments, I usually figure out what the function must implement. The next step is to copy the relevant lines to my editor and build the function from there.

Copying them one by one is cumbersome and copying them all at once will include the shell preffix and the outputs, so I’d need to clean that up after pasting into my editor. In cases like this, I use the magic %hist command:

It ouputs only the expressions I typed in (no prefix and no outputs), so now I can just copy those into my editor, cut out the irrelevant parts of the experiments and finally polish the implementation.

This commmand also allows to save the history directly into a file by running:

>>> %hist -f myscript.py 5-25

The command above will save all the statements from the input lines 5 to 25 into the myscript.py file.

Some people refer to this process as REPL driven development. I find it particularly useful when I am writing a function to transform data from a known format to another.

What else?

There are also a couple other commands that I find pretty helpful, but that I don’t use very often:

%pycat file.py: to view a python file inside IPython with syntax-highlighting and pagination.%run file.py: to run a python file inside the current IPython session.%quickref: to view a quick reference about magic commands.

Running system commands from inside the shell

It’s quite common to need to run an external command when you’re into an IPython session. Let’s say you want to quickly list the files from the current directory and you don’t want to leave your IPython session for that. All you have to do is this:

>>> !ls

main.py main.pyc output.txt

What’s even cooler is that you can assign a name to the output of the system command:

>>> files = !ls

>>> files

['main.py', 'main.pyc', 'output.txt']

>>> files.s

'main.py main.pyc output.txt'

>>> files.n

'main.py\nmain.pyc\noutput.txt'

>>> files.p

[PosixPath('main.py'), PosixPath('main.pyc'), PosixPath('output.txt')]

Of course this is not valid Python code, so you can’t just use !ls in your regular python scripts, but it can be pretty helpful during experiments.

Inspecting code with IPython

Sometimes I need to stop the execution of my app at a certain point to inspect what’s going on. Even though debuggers serve this exact purpose very well, IPython also allows to drop the line below into any Python script and it will stop its execution for you to inspect the context and run experiments:

from IPython import embed; embed()

Does this replace a full-fledged debugger? Not at all, but it can be pretty handy. If you want a debugger, check out this blog post that I wrote on pudb.

Wrapping up

IPython is super powerful and I am sure that there are tons of goodies that I am not even aware of, specially when it comes to notebooks and scientific computing.

The tricks that I shared here are useful for me in my daily life as a software developer and I hope some of them can be helpful to you.

P.S.: this post was heavily inspired by a talk given by my good friend Elias Dorneles and I back in 2016.